'CRISPR 2.0' Used To Change Patient's DNA For First Time

BY: RYAN CROSS TECHNOCRACY NEWS

Known as base editing, the technology empowers researchers to pick a single letter amongst the three billion that compose the human genome, erase it, and write a new letter in its place.

Base editing is an updated version of the gene editing tool CRISPR, which has revolutionized life sciences research and is making strides in treating genetic blood and liver diseases. But some scientists think base editing, sometimes billed as CRISPR 2.0, could be safer and more precise than the original. And this summer, the sequel technology is being used in patients for the first time.

On Tuesday, the Boston biotech firm Verve Therapeutics announced that it had edited the DNA of a person with a genetic condition that causes high cholesterol and predisposes them to heart disease. The base editor is designed to tweak a gene in the liver, curtail the accumulation of cholesterol, and hopefully lower the risk of heart attacks.

Verve chief executive and cofounder Sekar Kathiresan likens the approach to "surgery without a scalpel." Although the trial is focused on people with the genetic condition familial hypercholesterolemia, Kathiresan hopes that the one-and-done therapy may one day be used more broadly, to permanently reduce the risk of heart disease in millions of people with high cholesterol. "We are completely trying to rewrite how this disease is cared for," he said.

Base editing is making its way into studies for other conditions as well. Earlier this year, researchers at University College London quietly began a clinical trial using base editors to engineer immune cell therapies for leukemia — likely the first time base editors were used as part of any experimental medicine. And Cambridge firm Beam Therapeutics plans to use base editors to treat people with genetic blood diseases in a trial that will launch later this year. The firm also has early stage programs for cancer, liver disease, immune disorders, and vision loss.

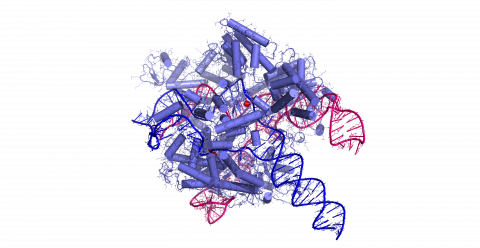

The powerful tool that could make all these treatments possible was first conceived by David Liu at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard in 2013, when he realized that CRISPR was not a panacea. CRISPR acts like a pair of molecular scissors that cut specific sequences of DNA. While that’s useful for turning problematic genes off, it doesn’t help to fix them.

“We really need ways to correct genes, not just disrupt them,” said Liu. “And that’s where base editing comes in.”

Liu’s base editors are modified versions of CRISPR that act like molecular erasers and pencils, swapping one of the four bases, or letters, of DNA for another. One version, developed by his postdoctoral researcher Alexis Komor in 2016, converts a C into a T. A second base editor, developed by his graduate student Nicole Gaudelli in 2017, changes an A into a G.

Comments

CRISPR 2.0

Comment